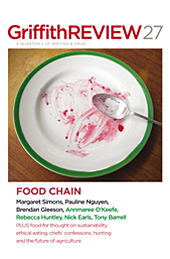

Featured in

- Published 20100302

- ISBN: 9781921520860

- Extent: 264 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm)

WHEN I WAS growing up, in the 1960s, the food we ate and its supply was tangible – literally outside the dining room window.

We had cows for milk and cream; sheep that grew from suckling lambs to Sunday lunch, and almost every other meal of the week; chickens we nursed in front of the fire, until they became chooks whose eggs we ate and whose feathers we plucked, when their recently headless bodies stopped the mad dervish dance down by the woodpile; vegetables that still had clods of dirt on them when they reached the kitchen; and fruit that fell from the trees, but for most of the year came from Fowlers Vacola jars deep in the pantry, an out-of-season topping for cereal or the base of the nightly dessert.

There was nothing sentimental about this. Our animals were not pets – they were creatures that fed us, and that could be trucked to the saleyard for a few dollars to pay pressing bills. It was smelly, dirty, unrelenting hard work, even on the fertile plains of Victoria’s Western District.

Most of the time we ate what my father produced, and my mother cooked. We did not think that we were fortunate; it was the way life was. Food came from the ground; it was seasonal, predictable and, apart from the occasional pavlova or brandy snap, pretty boring. Even our city cousins had chooks in their yards – those in the southern states had trees laden with mandarins, apples, almonds, plums and apricots, and the northerners had backyard trees that produced mysterious soft-skinned mangoes, pawpaws and bananas.

Occasionally we glimpsed another world. Family friends, who owned a big farm nearby, would load us into their two-toned, finned Chevrolet and take us to town, seven miles up the road. It was a special treat and signalled that the cheque for their fine wool had arrived.

There in Penshurst’s main street, in the dark and dusty milk bar, they would buy us Chiko rolls, Violet Crumble bars, Cheezels and Tarax soft drinks and laugh, in a kindly way, as we devoured this exotic food with an alertness to texture, flavour and packaging worthy of a Michelin Guide assessor. The crispness of the batter and the ooze of filling in the Chiko roll was unlike anything we ate at home; the tongue fizz of the Violet Crumble bore no relation to the honeycomb we made with golden syrup and bicarb soda; the sharp bubbles of the soft drink were shockingly different to the fresh orange juice we drank, without second thoughts, every day. Cheezels were clearly morsels from another world…

I recall furtive conversations later at home in the manse with my sister. ‘This must be the food rich people eat; if only we lived in the city we could eat this stuff all the time.’

We were wrong, of course.

Rich city people are much more likely to want to consume the food we grew up with – local, seasonal and organic. Poor people – including poor rural people, who make up a disproportionate number of the total – are much more likely to eat the cheap, mass-produced and packaged sustenance sold in convenience stores.

It is nonetheless easy to understand our misapprehension.

Entreaties to eat what was on the plate, and think about the starving children in India, rang in our ears. Every year we enthusiastically engaged in Freedom from Hunger drives that filled the church-hall kitchen with countless tins of powdered milk that disappeared to mysterious destinations. (‘Do poor people in India need Nestlé’s powdered milk because cows are sacred for them?’ we wondered.)

The disconnection between food production and consumption, between the food available to the rich and the rest, is now a matter of global anxiety. It is set to become more pronounced as the world’s population soars to nine billion and global warming disrupts traditional weather patterns. The Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that there are at least nine hundred million people without enough to eat every day. Even in developed countries, despite an epidemic of obesity, a shockingly large number of people go hungry – forty-nine million people in America alone in 2009.

The enormousness of the problem makes it hard not to be pessimistic. A more enlightened approach to feeding the world’s hungry – by giving them the tools for sustainable production rather than having them wait for shipments of instant noodles or powdered milk – is producing impressive results, but the challenge looms like a threat.

Food production and food security will be a bellwether of climate change. There is a lot of talk about rising sea levels, energy costs and extreme weather, but the price and supply of food will bring the reality home. As more than half the world’s population now lives in cities, urban food production will overtake the rural-peasant allotment of old.

After decades of detaching food production from the cities, all the major centres now have well-advanced plans to create city gardens. This is a throwback to the time when what are now inner-city botanical gardens were the food source of the colony, and regulations are being loosened to allow backyard chooks and encourage people to plant nature strips with fruit-bearing trees, herbs and vegetables.

Even in Australia, a country with abundant supplies of quality food, anxiety is growing. Talk about water allocations and licences masks the truth of a diminishing harvest from much of the Murray-Darling. Senator Bill Heffernan’s advocacy of the deeply embedded dream of a northern food bowl is less the reassertion of a national fantasy than a farmer’s intimate understanding of the connection between production and consumption. The ambitious plan to make Tasmania the new national food bowl is the product of original thinking not constrained by established verities.

WHEN MY FAMILY moved to the city, in 1971, we were unwittingly a part of the final phase of the great economic and social transformations of Australia from an agricultural economy to something else. At the time, baby boomers thought that they were escaping to a more interesting life in the city. Their parents could see that the days on the land were numbered – that an era was coming to an end, and the future was uncertain.

The relocation to the city was a consequence of the upheaval in agricultural production – farms were aggregated and production professionalised; the supply chains from paddock to supermarket became more clearly defined. As a result, the nation’s food could be produced much more efficiently and be shipped vast distances and still be fresh and affordable. There was no longer a need for so many people to collect their own eggs, chop the heads off their chooks or milk their own cows.

A country which had made its wealth by shipping its agricultural products to the world, which rewarded its returning soldiers with (suboptimal) farmland and which grounded its sense of identity in the bush, was about to become unequivocally urban. The rural economy was no longer the backbone of the nation and, as farms aggregated, towns faded away and the gap between the country and the city widened.

The pressures of climate change and population growth are making people ever more aware that something has been lost in industrial food production. Now, agriculture accounts for less than 5 per cent of GDP – about the same as the creative industries.

If we are what we eat, Australia is profoundly different to the country of my ’60s childhood. These days we eat food that is grown here, much of it processed by large transnational companies with headquarters in Japan, Europe and America. We buy it from supermarkets and grizzle about the prices, and wonder if this is sustainable and flock to farmers’ markets. We book out the best restaurants and churn through a global village of ethnic cafés. Schoolchildren follow Michelle Obama’s and Stephanie Alexander’s example and plant organic gardens. Cookbooks sell in extraordinary numbers, and cooking programs win the television ratings.

Now we are on the path to another major transformation – one that reintegrates the production and consumption of fresh local food into much longer food chains. The major chains have started organic food shops, a glamorous reworking of the local greengrocer.

When I see my urbane father navigate his designer trolley through the stalls at the Victoria Market, it is clear that his journey to seek out fresh produce is every bit as visceral as it is for the émigrés manning the stalls – the Greek fishmongers, Italian deli owners, Vietnamese market gardeners.

For my mother, who took to the role of part-time-farmer’s wife reluctantly, the combination of fresh food from the market and the supermarket is infinitely more appealing than plucking chooks, or devising yet another meal drawn from a freezer overflowing with every imaginable part of the lamb she had watched us feed with a bottle.

My father’s contact with food-producing soil may now be second-hand, and confined to growing a few tomatoes and herbs, but the connection with fresh produce is as essential as it was decades ago – even in the middle of a big city.

Share article

More from author

Move very fast and break many things

EssayWHEN FACEBOOK TURNED ten in 2014, Mark Zuckerberg, the founder and nerdish face of the social network, announced that its motto would cease to...

More from this edition

Feeding the world

EssayNEVILLE SIMPSON IS not your typical cotton farmer. He doesn't hold a university degree, nor does he command tens of thousands of hectares. He...

Shopping for revolution

GR OnlineI'TS A MUNDANE household task: peel the shopping list off the fridge and take it to the shops. But if, like me, you were...

My happy Cold War summers

MemoirSINCE EARLY CHILDHOOD, I have had a certain perception of the Iron Curtain and the Cold War. Not because I showed particular interest in...