Featured in

- Published 20130305

- ISBN: 9781922079961

- Extent: 264 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

TASMANIA HAS NEVER been for the faint-hearted. Set against a majestic if somewhat eerie landscape, its often-bizarre political machinations emerge from a history with many tangled threads. One important strand that runs through our history is agriculture. Unlike the other colonies, which swung from the sheep’s back when minerals and manufacture attracted their attention, Tasmania (try as it might) never moved far from its rural roots. We are now beginning to celebrate our farming past and future, and a renaissance is emerging in Tasmania around agriculture and food. To realise its potential, developments in food and farming will need to be informed by civil, creative, constructive and critical conversations.

Such conversations are alluded to in Paul Keating’s book After Words (Allen & Unwin, 2011): ‘A void exists between the drum-roll of mechanisation with its cumulative power of science and the haphazard, explosive power of creativity and passion. Science is forever trying to undress nature while the artistic impulse is to be wrapped in it. While these approaches are different – perhaps often diametrically opposite – they inform related strands of thinking in ways that promote energy and vision’.

Beneath Keating’s quip lies a central challenge of our time; one that resonates strongly in Tasmania. How do societies bring the divergent together and harness such cumulative and haphazard powers? But there is more than science and art, or energy and vision at stake here. The rifts in Tasmanian society have a long history and will not be easily resolved. A new dialogue will need to include old ideological adversaries as well as the technical and creative. Such discussions can revitalise our state in ways that are hard to imagine.

Agriculture is a good place to start such imagining. While we will disagree on how and where it should be done, when we sit down to a meal it is undeniable how essential agriculture is. It is a foundation stone on which the quality of our lives rests. It is also the most influential innovation in human history.

About 10,000 years ago, the advent of agriculture catapulted Neolithic humans into a world of complex entanglements that are still playing out. Agriculture transformed societies, rapidly expanding trade, creating the possibility of cities and ceaseless innovation in art and culture. It also precipitated the rule of the many by the few, the degradation of fertile landscapes and new forms of social inequity. Agriculture made for much less nutritious diets than did hunting and gathering, and as people were packed together in walled cities, disease burgeoned. Life expectancy declined. But the efficiency of agriculture – its ability to reliably feed a growing population – meant that no society ever turned away from it.

This ancient history of agriculture crystallises our central point: we never really had the chance of simply picking between the good and the bad. They were invariably wrapped together, by unforeseen chains of cause and effect. As the chains have become longer and messier in the rapid-fire of global markets and technologies, our ability to predict consequences is worn away even further. The agricultural examples of unexpected consequences are innumerable. Biofuels sounded like such a good idea until the price of corn skyrocketed and people began to starve; until the remnant rainforests of southeast Asia were turned into palm oil plantations. Cane toads seemed an obvious chemical-free solution to a pest in Australian sugar plantations. However, as the green revolution of the 1960s and ’70s so powerfully demonstrated, many recent agricultural innovations did achieve their primary objective: Norman Borlaug’s contribution to agricultural science and plant breeding resulted in high-yielding, disease resistant crops that saved about a billion people from starvation. Borlaug and colleagues managed to find a very effective technological fix to overcome resource limitation.

Now, during the first quarter of the twenty-first century, the challenge to our agricultural and food systems is different. This time it is not just about increasing yields per area (even if this was achievable); it is about increasing productivity without additional resources, without negative environmental and social impacts; it is about the quality, equity and accessibility of our food and fibre products. And it is about the economic viability of our farmers who are such an important part of Tasmania’s social fabric and the legitimate custodians of much of our landscape.

As long as our farming sector is in crisis, so our society will be. Although we hanker for the quick fixes that the green revolution conditioned us to expect, we need to accept that we have probably used up most of the panaceas, final solutions and silver bullets. But complexity need not prevent invention. Rather we can use it to dispel the myth that we have control, or that any individual or group among us knows the outcomes of our actions. We should let our collective experience of failure to predict erode our hubris and bolster our humility. This should encourage us to include a wider range of voices in our conversations about innovation and so find new ways to continually re-invent our futures.

In years to come it is very likely that agriculture will get more of our attention. It will take unprecedented efforts to increase global food production by 70 per cent to feed the projected global population of nine billion in 2050. Yet the long view will always be secondary to our immediate concerns. For instance, today we face falling returns at the farm gate as a soaring dollar tempts the large vegetable processors to import New Zealand produce to feed their factories. Rising transport costs are encouraging some processors to desert their suppliers. Farmers will often tell you that such financial pressures make it hard to look after the land as well as they would like to. ‘It’s hard to be green when you’re in the red’ is shorthand for the sorts of trade-offs that farmers face in their daily decisions between immediate cash-flow and long-term sustainability. Inevitably, global drivers of land management will lead to debates and contention, opportunities and risks, preservation and destruction.

IN ADVANCED MODERN economies where farmers make up such a small sector of the population, such issues are often ignored in the media and by society. Less so in Tasmania. It is the state of Australia in which the population is least urban, and the one in which agriculture, comprising about one fifth of the state domestic product, is most economically important. In fact, Tasmania’s reliance on agriculture is greater than any other fully developed economy that we are aware of.

Food, agriculture and our relationship with the land have always been central to the Tasmanian story. The chain of events that followed Lieutenant Bowen’s landing in Risdon Cove in 1803 transformed the island and shaped the views of its inhabitants in ways that are unusual, if not unique in the world. But farming in Tasmania has a much longer history. As agriculture was emerging in the Fertile Crescent ten thousand years ago, the glaciers of the Tasmanian highlands were finally receding. The sea had risen once again over the Bassian Plain to create an island. Using what Rhys Jones called ‘firestick farming’ (1969, Australian Natural History) the first Tasmanians managed mosaics of vast productive meadows through much of eastern and central Tasmania.Jones’ term conceives ‘farming’ broadly – it encompasses intentional management of land to create the conditions that feed and clothe people. It was exactly this management that attracted early settlers from Britain. They saw the promise of the grasslands, but it would take time to superimpose English agriculture onto the fire-streaked plains of the island. As James Boyce demonstrates in this book Van Diemen’s Land (Black Inc, 2008)the earliest days of the Van Diemonian period were characterised by the adoption of hunter-gatherer ways as the colonial authorities sought to feed the population. Unlike New South Wales where strict controls were enforced, in Van Diemen’s Land convicts were given leave to gather victuals for this ‘kangaroo economy’. By Boyce’s account, these peculiarities of a fledgling colony laid the seeds of a distinct Van Diemonian culture.

‘For a surprising number of current and former convicts, food clothing and shelter were to come not from the payment of wages, prescribed rations or charity, but to be the gift of the land itself. For men and women who had known poverty, harsh penal discipline, and autocratic masters and officials, success was not gauged by the accumulation of capital but rather by self-sufficiency and the extent to which one could preserve life and freedom.’

The hardy culture of men and women living in the bush, if not with Aborigines then usually with some indigenous knowledge, was later counterpoised against a class of agricultural settlers with wealth beyond imaging. The first of them were granted acreage equal to their bank balances. One could, of course, borrow briefly to top up the account from say five to ten thousand pounds, and be granted an estate the size of a small English county. With cheap labour the landed settlers built agricultural and political empires, some of which persist to this day. One would think that, in the face of such disparity, a class-riven society was near inevitable. Yet, in A Short History of Australia (Mentor, 1963), Manning Clark notes that discontent in Van Diemen’s Land was insignificant compared to the upheaval experienced in the colony of New South Wales. Boyce argues that the environment itself provides the key to understanding these differences between New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land: it ‘was not the quantity of bounty, but its availability to those without capital’. On the dingo-free island, game was easily accessible to anyone with a hunting dog. And even when the settlers were granted the prime land, the emancipists and native-born could and did carve out a simple living on the rougher blocks. Boyce eloquently lays out how this quiet, self-sufficient underclass of ‘Van Diemonians’ developed a strong relationship with the land from the outset. Among other things, he suggests that this love of the land would much later seed a new form of environmental politics, and thereby the Greens.

WHETHER THE ROOTS are Van Demonian or more recent, contemporary Tasmanians have both a strong affinity with our wild landscapes, and a sense that we must capitalise on our natural resource base to create a viable economy. These core values have precipitated remarkable and paradoxical things in the state: hydro-industrialisation gave birth to the world’s first green party; industrial agriculture set against an intimacy with the Tasmanian bush led Bill Mollison to develop permaculture; a proposed pulp mill in the Tamar Valley consolidated a regional vision in which small-scale agriculture, food, wine and tourism are seen as central to success. Tasmania has long been a place where strong, often myopic opinions have collided with intensity reminiscent of a dysfunctional family. The disciplinarian parents and the rebellious children are fortunately both growing up. There are signs that they are starting to look at the condition of the stunning home they somehow inherited, rather than reacting to each other’s antics.

Some say of this place that it is ‘small enough to manage, and big enough to matter’. And we do have a potential to evolve beyond our adversarial and exclusionary past. It will not be easy to get rid of our self-destructive habits that might once have served a purpose. The lessons of forestry, and the proposed pulp mill point to the need to build social license through commitments to transparency and good processes around specific issues. And though the term ‘social licence’ is now part of normal conversation, the question of how to get one remains elusive. We suggest that social license arises when citizens are engaged well on issues that are important to them, when they are meaningfully included in deliberating and deciding. Our state governments have experimented with wide-scale processes of engaging Tasmanians in the past. A prime example is ‘Tasmania Together’ – an attempt to give citizens a say in how we can work from a base of values to create a vision and set community goals for the future for the state. Such processes, while laudable, have tended to put more in our mouths than we can chew, and so we ended up gagging.

Here we can again learn from agriculture, and particularly the processes and practitioners that enable change in rural communities. Such people and processes bring together scientific and local knowledge to create targeted ways of innovating or addressing specific problems at appropriate scales. They can create conduits or bridges and play key roles in convening focused meetings, mediating differences, and translating knowledge into practical options for decision-makers.

This work is integral to the vibrant rural enterprises that still flourish in Tasmania, despite the unfavourable terms of trade. Such businesses capitalise, for instance, on the natural advantage of our relatively long, cool growing season. The slowness of the season means that plants in Tasmania build their fruit and foliage more gradually than their northern counterparts and so fill them with more sugars and complex flavours. Our cool-climate wine industry demands a premium average export price of $13.16 per litre, compared to the Australia average of $2.61 (2011-12 figures). Similarly, our boutique dairy and other fine food producers are gaining world renown, while our poppy industry supplies more than 50 per cent of all global alkaloids produced for the pharmaceutical industry. These industries epitomise an ability to mix applied science and technology with artisanal skill, creativity and passion. They speak in very practical ways to the gulf Paul Keating described.

In Tasmania, conversations which bridge our historical and contemporary divides are becoming increasingly eclectic. We are beginning to bring together odd bedfellows: scientists, artists, farmers and environmentalists. As one of the few remaining places in the global north where agriculture still underpins the economy; as the home to a disproportionately large and vibrant community of artists; as a place where science happens at least slightly closer to society than most, we have an opportunity to begin building bridges over the treacherous voids that Keating lamented. In Tasmania, the canyons may be deep but they are also quite narrow. They may yet be bridged.

Images: Jesse Eynon’s recent paintings stem from her fascination with the light and theatre of rural Tasmanian landscape.

Share article

About the author

Peat Leith

Peat Leith is a Research Fellow at the Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture (TIA) and the Institute of Marine and Antarctic Studies, both at the...

More from this edition

Censored conversations

MemoirA DOG runs up to my husband on a windswept beach on Sunday morning. Tess is a Jack Russell cross, caramel and white and...

Tasmanian gothic

EssaySOME DARK SECRETS run so deep that they slip from view. The hole left in our collective conscience is gradually plugged, with shallow distractions...

Oscillating wildly

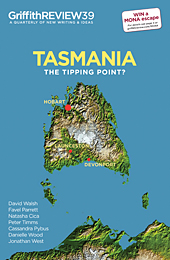

IntroductionTASMANIA OCCUPIES A unique place in the national imagination. It is different in so many ways to the vast, dry expanses of the continent...