Featured in

- Published 20130305

- ISBN: 9781922079961

- Extent: 264 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

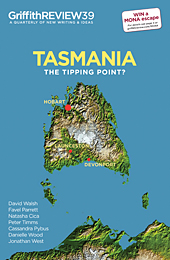

TASMANIA IS VIEWED by many Australians who don’t live on the island as some kind of paradise. The traffic is slower and there is less of it. The breathtaking physical beauty of the place is rarely more than five minutes away and the cultural offerings like food, wine and art can be fairly described as luxuriant. But the notion of a paradise only has resonance if you are comfortably middle class or higher up the income ladder. For around a third of people who reside in Tasmania life is unrelentingly difficult. For this group of Tasmanians, dispossession, deprivation and a bleak horizon are the hallmarks of the average day.

The idyllic Tasmania of travel magazines and lifestyle programmes is beyond the reach of around one hundred and fifty thousand Tasmanians who survive – it would be wrong to say that they ‘live’ – on Newstart Allowance, the Disability Support Pension or other forms of Centrelink payments.

While politicians and community leaders have for many years now talked the talk about alleviating poverty and making a dent in the level of welfare recipients, little has been achieved. Even during Tasmania’s recent economic boom, that spanned from around 2000 to the GFC in 2008, this group of excluded Tasmanians did not share in the benefits. Most of them remain outside the workforce, their children still leave school at Year 10, they are disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system and the rates of mental and physical illness among this cohort of Tasmanians remains stubbornly high.

Paradoxically, however, it is Tasmanians for whom welfare payments are the major source of income that provide the best chance for this fragile society and economy to have any hope of becoming less reliant on Commonwealth handouts in the future. If more Tasmanians were able to work and own businesses, the higher would be the economic growth and the lower would be the social dislocation.

Think of it this way: In Tasmania there are many men, women and children who at the moment are underutilised by the society in which they live.

Until Tasmania finds ways to address the inherent injustice of having so many of its citizens excluded from progress by virtue of their income status, then it will remain this Janus-faced society – the crystal clear waters draped across the cover of the coffee table book versus the bleak suburban streets of outer Hobart, Launceston and the northwest coast.

IN DISCUSSING HOW it might be possible to radically alter the nature of Tasmanian society by unleashing the human capital of excluded Tasmanians, one has to ask why it is that the status quo has existed since the state’s hydroelectricity-driven industrial boom came to a halt in the 1970s.

The state itself must shoulder much of the blame. It is characterised by two features. First, it is a paternalistic state, particularly in the areas of welfare. Second, interest groups have easy access to politicians and the latter generally cannot resist the demands of the former if they make enough noise. This second characteristic leads to poor public policy outcomes and misallocation of scarce budgetary resources.

That Tasmanian government officials are paternalist and disempowering is evident daily in the way in which families are dealt with by the child protection authorities. As a barrister, I have acted for many parents who have had their children removed by the state or who are under threat of the state doing so. With few exceptions these parents are part of that marginalised group of Tasmanians who depend on welfare as their primary source of income. The demeanour and actions of child protection workers generally, and there are of course notable exceptions, is one of punishment and misunderstanding. The language and attitudes of my clients reflect their state but they are seen as being poor parents. Nearly all parents who journey through the child protection system in Tasmania feel embittered or disheartened. There is no sense on the part of government officials that the lives of these people could be any different from what they are today.

The second characteristic, that of undue influence of policy by interest groups in Tasmania, is an equally damaging one for marginalised Tasmanians. Handouts to the private sector and millions of dollars spent on the Hawthorn Football Club are the most egregious examples of a political culture that rewards lobbying by the powerful (Hawthorn, the highly successful, well-heeled Australian Rules club convinced the Tasmanian government around six years ago that the latter ought to part with millions of dollars in exchange for which Hawthorn would play some matches in Launceston and the Tasmania logo would be worn on the Hawthorn players’ guernseys). Then there are vested interest groups such as the union movement (as a wise observer once said to me, the unions don’t care about the unemployed because they are not members). When, for example, the current ALP government of Premier Lara Giddings proposed merging schools that were substandard or otherwise unviable, the education unions combined with parent groups to stymie the reform. The losers were parents in low-income areas, where many of the substandard schools are located.

In sum then, it would be foolish for any person with an interest in reducing social and economic inequality in Tasmania to expect the lead to come from government. The solutions must lie within communities themselves and within the individuals who live in marginalised areas. All that can be expected from government is that it does impede reforms. That it does not, in its paternalist fashion, meddle with community-driven approaches through ridiculous red tape or by imposing outlandish requirements.

In advocating for the marginalised in Tasmania over the past decade, I have been struck by just how many resilient and clever people live within these communities. These are individuals who would make ideal community leaders because they are respected by their neighbours and they have a network of friends in the community in which they live. It is that strength which needs to be given an opportunity to grow and to lead others.

THERE ARE PLENTY of examples from which Tasmanian communities can borrow, particularly in the United States. The latter is particularly relevant given the culture of individualism and less reliance by communities on the state for support.

While the industrial mid-west US state of Michigan might not appear at first blush to have much relevance for Tasmania, some of its communities have much in common with disadvantaged areas of Tasmania. Traverse Bay, with a population of around 13,000, in northwest Michigan, is a case in point. Like many parts of Tasmania, Traverse Bay has been a victim of the same chill winds of globalisation that have seen small to medium-sized manufacturing businesses head offshore to take advantage of lower labour costs. And, like regional Tasmania, Traverse Bay’s wine and tourism industries are seen as sources of future wealth for a region that has been hollowed out. These industries, however, only employ small numbers of people and often the employment is menial.

In 2004, a group of people from the Traverse Bay region gathered for what was termed a ‘poverty summit’. They regaled their neighbours with stories about how poverty affected them, their families and neighbourhoods. The summit came up with priorities for reducing poverty and the top five areas that needed to be addressed were jobs, education, health care, housing and attitudes in the region. The philosophy of the summit was that it would look inwards for support – that is, tap into the talents and skills of groups and individuals in the community.

Eight years on and the Traverse Bay Poverty Reduction Initiative is still going. The Michigan State University provides some research and talent grunt and local businesses are involved. There are a number of activities which aim to help reduce poverty and, importantly, encourage those trapped in marginalised lifestyles to have the confidence to take risks.

The beauty of the Traverse Bay style of community-driven poverty alleviation and enterprise building is that it provides solutions which are easily accessible to most people. There is a loan program run by a small financial organisation which was created by low-income earners and which lends to low-income earners. There is a free laundry service. One of the local financial groups has established a Sunday evening meeting every second month for school children to teach financial literacy and budgeting. On Saturdays there are classes in cooking and other domestic activities. There are leadership programs and conferences to work with people on making positive changes in their lives.

That the Traverse Bay Poverty Reduction Initiative is thriving after eight years has inspired another Michigan community to launch a similar organisation. Kalamazoo has also lost jobs which will never return because the factories have closed forever. It has modelled its poverty reduction initiative on Traverse Bay’s and has opened a small bank for residents in the city. Over the border in Calgary, Canada, a poverty reduction initiative began its work in 2012.

THE BOTTOM-UP POVERTY reduction initiative approach of Traverse Bay represents a new approach to poverty alleviation and, importantly, poverty prevention in Tasmania. It is an idea that relies not on government, at least at the state level, but on communities themselves coalescing around a set of ideals and practical outcomes for those who need this assistance. At a very basic level, it means doing something like creating a car transport service so that young single mothers who miss a bus do not have to miss important appointments for themselves or their children. Or providing finance to a young person who loves cars and wants to establish a car detailing business. At a higher level it is about the community itself declaring war on poverty and beginning to change the perception of that community in government and broader circles.

A community-led poverty reduction initiative in Tasmania circumvents the political and government cultural issues referred to earlier. That is, it does not require dealing with government departments and the paternalist culture which goes with such interactions. And there is no need for lobbying of government for scarce funds. A poverty reduction initiative is funded outside of government.

The entrenched poverty and economic and social disadvantage that has taken hold in many regions in Tasmania can only be shifted in a long-term and sustainable sense by community-led agitation and action of the type that the communities of Traverse Bay, Kalamazoo and Calgary are undertaking. This is because there seems to be an acceptance, albeit unwitting, on the part of government and even many Tasmanians that Jesus Christ’s observation in Matthew’s Gospel, ‘the poor you will always have with you’ is to be taken literally and therefore there is little that can be done to change the established order of things.

Tasmania is not simply a land of paradise to which Australians from the mainland retreat. Its physical beauty and cultural assets cannot be allowed to mask the deprivation and marginalisation to which many on this island of just over half a million people are subjected. A paradise will only truly exist if there is a substantial reduction in the number of Tasmanians on welfare payments because a culture of opportunity and initiative emerges.

Share article

More from author

Orchestrating the myth

EssayIN OCTOBER 1938, the state-controlled German newspaper Berliner Zeitung am Mittag carried this headline, "In der Staatsoper: Das Wunder Karajan" (In the State Opera,...

More from this edition

Big thought and a small island

GR OnlineTHIS STORY STARTS, as many good stories do, with a conversation between a taxi driver and a customer. In this case, the trip was...

Remembering 1939

GR OnlineI STILL COULDN'T' get my head around landing. Perhaps it was the economics; Australia, after all, had been all but immune to Europe's recent...

The cracks are how the light gets in

EssayTASMANIANS BANG ON about 'place' a lot – at least some of us do. Maybe because Tasmania can be so affecting and beautiful, as...