Featured in

- Published 20130604

- ISBN: 9781922079978

- Extent: 288 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

THIS IS A singular history of drinking – within one Costello family of Irish, French, Spanish and/or Italian ancestry, all of whom have associations with alcohol.

But our first drink every day was warm water with freshly squeezed lemon juice. It was our father Frank’s legacy, as are most, if not all, of our drinking habits. We probably had a lemon tree in the backyard, along with stone fruit, a choko vine, rotary clothes line, cubby house, shed, incinerator, fish pond, chooks and dogs, canaries, budgerigars and homing pigeons. Lemon cleansed the body, leaving the mouth stripped bare and scouring the soul temporarily white, ready for the day ahead. Toxins dissipated and life began anew. It was like spring every morning. However, it didn’t save our father from a relatively early death at seventy-six. Lemons are incapable of counter-terrorism against tobacco.

The blood of Christ was our next memorable beverage. In the sacrament of the Eucharist, the bread and wine are transubstantiated into the body and blood of Christ. We consumed them at Sunday morning Mass, at the glorious rose-and-cream marble communion rail of St Mark’s Church, Drummoyne. It’s a wonder we weren’t horrified by the cannibalistic implications of the practice. But the host was swallowed, by-passing the teeth. And we had been seduced by the metrosexual images of Christ with long, wavy hair, so common to the period. Or perhaps our capacity for horror had a high threshold because of the sadistic tales of the persecution of saints by beating, burning or dismemberment, or all three, in our primary-school religion lessons.

The parish priest, Father Boyle, managed to deliver just the tiniest sip of wine to a rail full of communicants, wiping the gold chalice with a white cloth and moving on. The wine tasted like what we now recognise as port, sherry, or bulk red, but we’re uncertain of its flavour because there were so many other distractions for teenage girls at Communion, like seeing what other girls were wearing. With hands cupped in prayer mode at the chest, but looking piously to the ground, we had to remember where we sat in a large and crowded church with undifferentiated seating of heavy, dark wooden pews. It could be competitive, embarrassing, mortifying. Unfortunately, it was never intoxicating: too little wine offered and too big a leap of faith required.

Our third encounter with drinking was our father coming home from a Friday-night swill, which has a long history for Australian workers, from early evening six o’clock pub closures to the present day of very late nights or early mornings. Sometimes Frank would knock at the door to announce his beer-soaked arrival. Why bother with keys? He had a large contingent of women behind the home door. His present of family packs of Cadbury chocolate paved the way for forgiveness by Joyce, our mother, and soothed the spirits of his four daughters draped in flannelette pajamas and chenille dressing-gowns.

Sunday lunches after Mass were a process of setting the table with an array of cutlery, plates, glasses and an ironed tablecloth embroidered by Joyce. The peas had been popped, the potatoes peeled. Frank carved the roast. One of us would have bought the roast, under Joyce’s instructive shopping list, from the local, lecherous butchers. They worked with flesh, bone, blood, sawdust to soak up the blood and sharp knives. Handsome yes, but extremely disturbing with their suggestive questions and comments for young girls-becoming-women. At some point Patricia heard that the butchers had porn film nights upstairs at the back of the shop. And that’s when she refused to buy the meat. In the longer term, Patricia became a vegetarian, but has never given up drinking.

A longneck of stout, Reschs DA or Tooth’s KB, was a requisite pre-lunch drink for Frank, post-counting the Sunday Mass collection plates of notes and coins from St Mark’s parishioners. Frank lunched with another glass of beer or ‘tinny’. The beers were light-golden brown, topped with white froth, just like Sydney’s beaches. One beer led to another, just like Sydney’s beaches, either north, south or east: Whale to Palm, Wanda to Cronulla, Bondi to Clovelly.

We like beer because it’s bubbly, refreshingly cool from the tap or in glasses from the freezer, and because it never fails to remind us of an Australian summer of sun, sand, surf and fish and chips. On a Friday evening, all the Drummoyne Catholics – the Bakers, Cliffords, Connollys, Kennedys, Sharples, Smiths and Tierneys – came to the local fish-and-chip shop for the take-away evening meal. Fortunately for Frank, it was adjacent to the Birkenhead Hotel. We lived next door to a barmaid who worked at another Drummoyne pub, the Oxford. We knew Drummoyne’s pubs because they were Frank’s ‘watering holes’. He also drank at the Drummoyne Sailing Club and Drummoyne Rowing Club, both on the Parramatta River. He looked out from our back verandah to the sunset over that distant river and asked why anyone would want to travel overseas, when we had it all here.

When the fish and chips were frying, Moya would sit with a lemon squash on the steps of the pub, while Frank enjoyed the brown amber with his mates at the bar. She had an excitingly strange view onto an adult world: when the pub’s bar-room doors swung open, she saw Frank talking and joking, grasping his beer, the strong smell of yeast and hops drifting out into the street. In Australian pubs, women were relegated to the Ladies’ Lounge.

Patricia remembers the first taste of brown bubbles as an elusive want of something that only adults could consume: when the beer bubbles started flowing, inquisitiveness started growing. The Birkenhead was lax then. With her high-school friends, she’d have illegal tap beers, Bacardi and Coke, or cheap bourbon. ‘Now Frank, don’t be giving her a taste of your beer … It will turn her into an alcoholic!’ This was speechifying from Joyce, a tea-swizzling suburban mum with a taste for Ben Ean Moselle and Porphyry Pearl drunk at Christmas-present exchanges at our neighbour’s place, the Spellacys, past the blue hydrangea and through the adjoining gate of our backyards.

At Christmas celebrations at home, Joyce famously made the luscious, sweet, creamy cocktails: Strawberry Blondes and Brandy Alexanders made of ice-cream, cream, maraschino cherries, strawberries, brandy, Coke and creme de cacao (white and brown). Patricia is a strawberry-blonde.

As an adolescent, Patricia made out on the front lawn of home or on the school grounds (when closed), after home parties or pub hang-outs. Joyce once interrupted a ‘party’ at Patricia’s best friend’s house and dragged her away (after a few beverages) when she spied her kissing a boy on the lounge. It was a night for both of them in more one ways than one – a standout in defining their parent-child relationship.

The next day, Patricia, due to take off on a trip to Whale Beach, for surf and sun, with the same party boys and girl, woke up with her bikini hidden somewhere. All she got to do was sit on the front steps of home and watch her mates take off in the VW Kombi while she was made to repent. It reminded her of the humiliation that neither Joyce nor she apologised for or even understood.

Joyce took to Chardonnay when Australian wine became more sophisticated. She avoided red, which Frank was never allowed to consume as it projected his dark side. Later still she returned to sherry drinking. When a liquor outlet opened up the road, she walked there regularly to buy a bottle of McWilliam’s Cream Sherry. One of Joyce’s famous stories, often repeated, was going into ‘town’, the CBD of Sydney, with Frank’s mother for some shopping, and afterwards our nanna suggesting they go for a sherry at a pub. Joyce was a little shocked but couldn’t resist the dissident behaviour. They would have drunk in a Ladies’ Lounge.

WHEN WE WERE grown up and living elsewhere, the four of us, as daughters, brought a variety of wine to the Christmas lunch table. A mixture of domestic and foreign wine coloured the glasses pale lemon, gold, pink and red. Our eldest sister bought domestic, Patricia, the youngest, French imports. Working in restaurants and bars provided Patricia with a background to these family get-togethers: a world of wine tastings and cocktail creations.

She collectswine for celebratory occasions under the bed in the spare room of herNorth Bondi Beach flat. Sometimes it’s undrinkable. Other times it’s like a Da Vinci opened up his world and the poetry of wine and decadence combine to form a joyous liquid to line the veins of a waiting chorus.

As girls, the four Costello daughters were housed in one room filled with a built-in wardrobe, a dressing-table, a double bunk and two single beds. Home was a single-fronted house of two main bedrooms for an extended family of fouradults and four children, with added enclosed back-verandah and under-house rooms. (When all of us as daughters eventually moved out of home, our own private bedrooms came as a revelation.)

Early one morning our second-oldest sister came home from a ball, for which Joyce had made a glamorous lemon-cream empire-line gown (probably from an up-to-the-minute ’70s Simplicity pattern). We woke in the early hours of the morning, as a young man helped her into our virginal bedroom. We gave her water and aspirin and tried to aid her in her attempts to prod her legs into the sleeves of her pajama top. We rumbled the home walls with laughter, and it was the first time Frank ever grounded, or would ever again ground, one of us. (He forever underestimated his patriarchal power.) Patricia always believed it was because Joyce was so disgusted with our sister’s behavior that Frank had to intervene. Otherwise, he was a kind of absent presence.

The first time Patricia vomited from alcohol, the cocktail involved was and still is called Americano, made from Campari, gin and vermouth. Joyce cleaned up after the sorry mess.

As young women, that second-oldest sister and Moya took a tour of the Hunter Valley wineries, and found themselves, incongruently, among Young Liberals. We were a Labor-voting family. Frank adored Gough Whitlam and Bob Hawke, and found Paul Keating’s gutter mouth amusing.

So it was 1991 that the then Prime Minister Paul Keating came to Zanzibar in the back of King’s Cross, where Patricia worked. It was only the beginning of new, fabulous restaurants in Sydney. Zanzibar was managed by a stylish French man named Jéan (of course) and, dedicated to him and his restaurant, Patricia worked well into the early morning serving the clientele. Keating’s PR, Baz Luhrmann, the now famous film director, a regular Zanzibar customer and friend to Jéan, brought PK’s entourage to the bar to celebrate winning the election. Everybody in the bar, from customers to staff, had voted Labor.

Patricia made Keating her own cocktail, named after one big night out with friends, associates and east-Sydney cohorts watching Barbarella. She devised the cocktail from thinking about a match for the tale of a mythical illusion of virginal women’s power. And to damn Roger Vadim, the film’s director. It was a mixture of Frangelico (fashionable at the time), Sambuca, orange and pineapple juice and a dash of lemon, shaken over ice and served in a martini glass. Keating loved it. Patricia rang Joyce at 2am to tell her that the new PM had just graced the establishment she worked in and drank her own cocktail. Joyce was very excited.

Merrony’s opened in early 1992, under the tall monolith of the Quay Apartments at Circular Quay. The restaurant drew the Who’s Who of Sydney. Gough Whitlam came to dine with Margaret. Patricia was working the bar area. Labor born and bred, Catholic to boot, booze for blood and not shy, Patricia shook his hand and discussed the virtues of Frangelico, the monks, the sweetness and delights of exploration, and the mastery that she and Gough were used to. She always bragged that she did not wash that hand for over a week.

Three of us and Joyce, after Frank’s death, would have lunches, including Christmas, cooked by now-famous chefs, Matt Moran, Damien Pignolet, David Rayner and Simon Lawson, with sommelier choices from superb wine lists to match the food, at some of Sydney’s best restaurants where Patricia worked, such as Moran’s, Potts Point; Bistro Moncur, Woollahra; Nove Cucina/Otto Ristorante, Woolloomooloo; and Vault, The Rocks. These times were special for Patricia, as they made up for her missing out on the private family moments when she’d be working the night shift or day-to-night doubles in the tumultuous hospitality industry.

Christmas working days were long and intense for Patricia, but fun. The same families attended annually. There was mirth, friendship, familiarity, gifts, food and drinking. And, of course, the day ended for the staff, Christmas orphans who hung around after service, with snacks from a three-course lunch and leftover bottles of vino which were then drained to the last drop. The Christmas orphans headed home to their separate fridges filled to the brim with delights and overstocked with booze.

One Christmas, a family, entrenched eastern-suburbs types via Brisbane and the Gold Coast, the patriarch a doctor on call, had a long and celebratory lunch. The bill arrived, and there were planes to catch. There was no tip left, but they were a funny and genuine group of people, so it was hard for Patricia to be disappointed. But one by one, as they left, each member of the family gave her something for her service. It was all a bit awkward. She kept insisting that everything had been taken care of. She and the staff sat around later and discussed how all of them would recall the joys of Christmas lunch and how lovely that waiter was and how they all made sure she was appreciated, but all of them not knowing that each of the golden handshakes were singular and that each one commented and apologised that the other had not left a gratuity. ‘I gave her a fifty.’ ‘I slipped her a pineapple.’ Patricia was ahead by more than $200 that day.

Within a year or two of Frank’s’ death, a friend of Patricia’s, Simon, transported her, our two sisters and Joyce along Parramatta Road into the depths of Rookwood Cemetery and back to another rowing club, at Haberfield, in memory of Frank. They passed an establishment called Hooters, its sign prominently accentuating the ‘oo’. Joyce asked what the establishment was and if they could eat there. In deft style, Simon said the Haberfield Rowing Club was booked, but he would take her to Hooters one day. They enjoyed the day on the water, at the far end of the emotional scale, with beer and wine to drown the inexplicable lightness of being.

Currently, Patricia hangs out at the local North Bondi RSL. It’s a great venue: fun, friendly, scenic and, above all walking distance from her flat. Beers are cold, wines are reasonably priced and the food is good tucker to fill an empty belly. She has spent many moments with Moya, with extended family members, Joyce’s sister and her husband, Pat and Phil; with musician mates, Tiare, muso in her own right and tour manager for the church, Jordan from Meow Kapow, DJs Scott Pullen and Andy Glitre; industry buddies and kids; and sometimes just by herself, enjoying the ambient view of the waves rolling in on the beach.

For over twenty years, Moya lived and drank in Adelaide, Australia’s wine capital. It’s there she decided wine-making was an art form. The Adelaide Hills, McLaren Vale, Coonawarra, Barossa and Clare Valleys produce among the best Australian, and international, wine. When your cup runs over where you are, there is no need to be a Hunter, Yarra, Derwent or Swan Valley drinker.

When, for work, she moved back to New South Wales, to the far North Coast, she had to realign her xenophobic statist tendencies and (re)discover the multiple and multiplying sources of Australia’s splendid wines. The Northern Rivers is sub-tropical and rain-soaked, not conducive to growing wine grapes. Nevertheless, the Northern Rivers Zone is the classification for wineries in the Hastings Valley Region, and further north are the Northern Slopes and, just across the border, the Queensland Zone. She writes wine reviews featuring these ‘local’ wines for The Northern Rivers Echo, a free regional newspaper before switching to The Village Journal; maintains blogs as a ‘locabiber’ and for general quaffing; writes academic research papers within the discipline of Food Studies; and teaches wine and food writing.

The two of us, Moya and Patricia, occasionally sit together on the idyllic verandah of an old Queenslander – an Australian architectural style for the tropics – on the property Moya owns with her partner in the north-coast hinterland. Here we hold personal wine tastings, arguing about colour, aroma and taste, in a kind of comic routine we could have easily performed with Frank. Patricia has introduced Moya to three Italian grapes: the delightful Prosecco, the blissful Arneis, and the more austere Verdiccho. We practically compete over our latest Rosé discovery: we’ve long passed Australian icons such as Charles Melton, and headed into the labyrinthine territory of a seemingly inexhaustible number of boutique labels such as Rogers and Rufus. We indulge in local alternative varieties: Fiano, Vermentino, Nebbiolo, Nero d’Avola. And we wonder at the revelation on our palates and spectacle before our eyes. Sunsets with butcher birds and magpies, noisy in the trees, form a theatrical backdrop to the popping of corks, the unscrewing of stelvin caps and the clinking of glasses.

‘I don’t remember’ is the embarrassingly petty yet hugely immoral alibi for crime by unethical politicians, financiers and industrialists; ‘I forget myself’ is the personal acknowledgement of ill-mannered behaviour; while ‘You won’t know yourself’ is the eccentric aphorism for a transformative experience. On the verandah, we indulge probably too much, according to Moya’s partner, Jeff, who had a Baptist-like non-alcoholic upbringing. But, after all, the Costello girls love a drink; it becomes us; and, through it, we become who we are.

Share article

More from this edition

The women are present

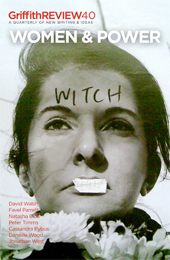

IntroductionIT DID NOT take long before posters advertising performance artist Marina Abramovic's show at New York's Museum of Modern Art were defaced – literally....

Sound the alarm

FictionTHERE'S THE TUG of it in her stomach, always, a heavy thing. Sarah's hot, clammy like she knows she shouldn't be on a day...

A bleak set of numbers

GR OnlineWHEN WARLPIRI WOMAN Bess Nungurrayi Price speaks about Aboriginal affairs she does so with a special authority rooted in the fact of her birth...